Peter Carril/ESA

- NASA simulated a scenario in which an asteroid was approaching Earth and would hit in six months.

- The experts determined that wasn't enough time to stop it. We'd need at least five years to deflect an asteroid.

- To have that much warning time, NASA needs a new space telescope that can spot asteroids.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

Last month, experts from NASA and other space agencies around the world faced a troubling hypothetical scenario: A mysterious asteroid had just been discovered 35 million miles away, and it was heading for Earth. The space rock was expected to hit in six months.

The situation was fictional, part of a week-long exercise that simulated an incoming asteroid in order to help US and international experts practice how to respond to such a situation.

The simulation taught the group a difficult lesson: If an Earth-bound asteroid were spotted with that little warning, there's nothing anyone could do to keep it from hitting the planet. The experts determined that no existing technologies could stop the asteroid from striking, given the scenario's six-month window. There isn't a spacecraft capable of destroying an asteroid or pushing it off its path that could get off the ground and fly to the rock in that amount of time.

Paul Chodas, manager of NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies, helped host the recent simulation, as well as five previous ones like it. He said this exercise set the participants up for failure.

"It's what we call a short-warning scenario," he told Insider. "It was, by design, very challenging."

In reality, if an asteroid like that fictional one were heading for Earth, scientists would need years - not months - of warning. Five years is the minimum, according to Chodas. Others, like MIT astronomer Richard Binzel, say we'd need at least a decade.

"Time is the most valuable commodity you could possibly wish for, if faced with a real asteroid threat," Binzel told Insider.

But scientists haven't identified most of the hazardous space rocks that pass near our planet, which makes the chances slim that we'd get a five- or 10-year warning period. In 2005, Congress attempted to address this issue by mandating that NASA find and track 90% of all near-Earth objects 140 meters (460 feet) or larger. At that size, asteroids could obliterate a city the size of New York. But to date, NASA has only spotted about 40% of those objects.

"What that means is, for now, we are relying on luck to keep us safe from major asteroid impacts," Binzel said. "But luck is not a plan."

To defend a planet, 'know thy enemy'

AP

In NASA's recent simulation, the participating scientists didn't know how big the hypothetical asteroid was until a week before it was set to hit Earth.

"We didn't know if the object was 35 meters across or 500 meters across. And that makes a very big difference," Sarah Sonnett, a researcher at the Planetary Science Institute who participated in the exercise, told Insider.

A 35-meter asteroid could explode in the atmosphere and send shockwaves through a neighborhood. A 500-meter asteroid could decimate a city, with an affecting an area the size of France.

So a crucial part of stopping an asteroid from hitting Earth is understanding as much as possible about the rock. That includes its size, the path it takes around the sun, and what it's made of. With that information, scientists can evaluate strategies to dismantle the rock or disrupt its path.

"It takes time to know thy enemy," Binzel said.

Ideally, Sonnett said, scientists would be able to study a hazardous asteroid as it passed Earth a few times in its orbit around the sun, before that path brought it close enough to collide with our planet. Observing a passing asteroid several times could take years or even decades.

Step 2: Destroy or deflect the asteroid

Reuters/NASA/JPL-Caltech/Handout

NASA has three main tools in its planetary-defense arsenal. The first is to detonate an explosive device near an oncoming asteroid to break it up into smaller, less dangerous chunks. The second is to fire lasers that could heat up and vaporize the space rock enough to change its orbital path. The third is to send a spacecraft to slam into the asteroid, knocking it off its trajectory.

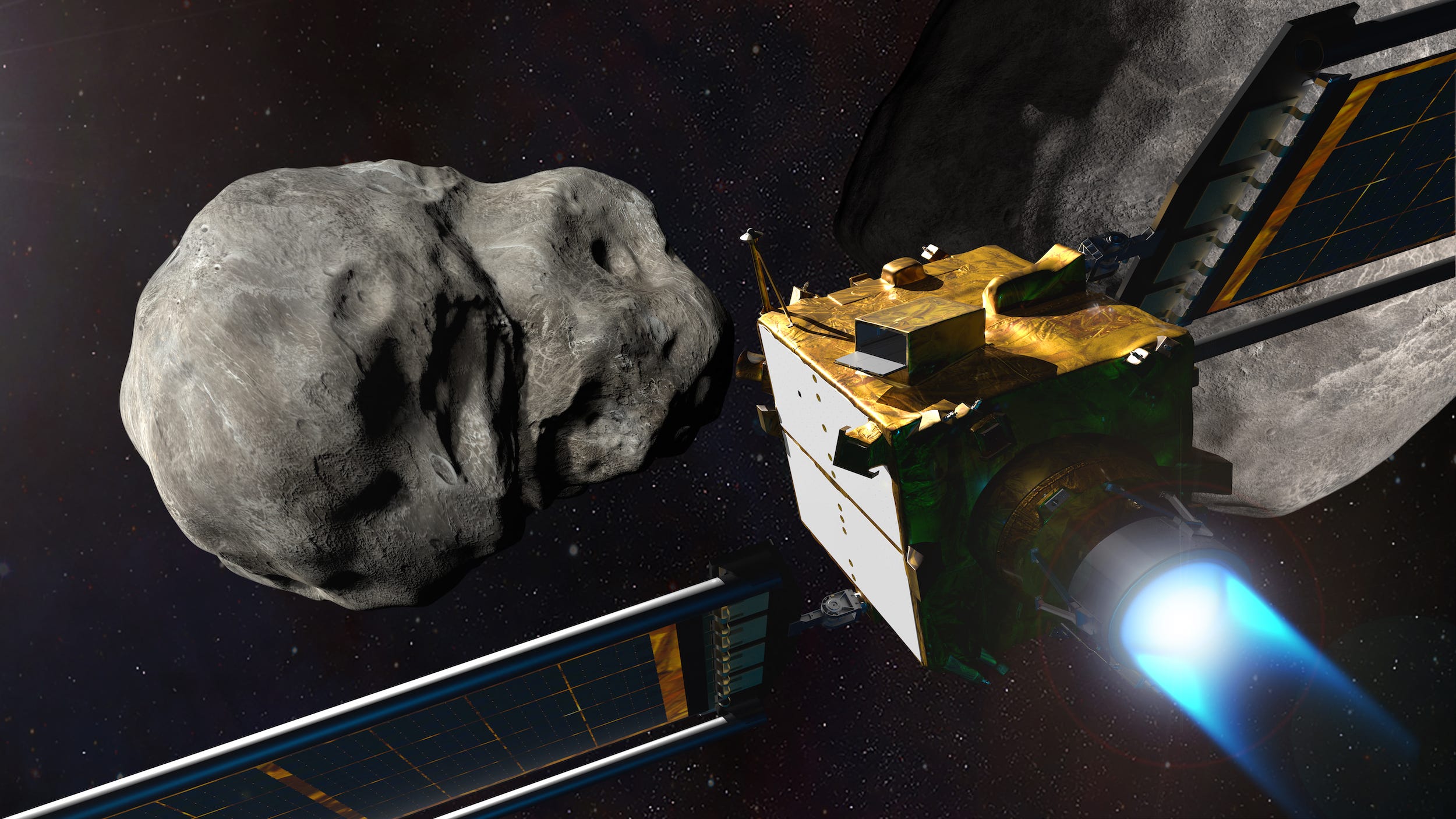

NASA is about to test that last strategy. Its Double Asteroid Redirection Test will send a probe to the asteroid Dimorphos in the fall of 2022 and purposefully hit it.

But any of the three options, Chodas said, would take years.

"Typically, that's a drawn-out, multi-year process to go from proposal to actually having a spacecraft on a launch vehicle - let alone the fact that you still have to cruise to get to your destination and deflect the asteroid," he said.

After that, it would take one or two years for the asteroid's path around the sun to actually change enough to carry it away from Earth. That's why the timeline matters: The earlier scientists can identify a hazardous space rock, the less ambitious a deflection mission would have to be.

NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

But of course, all of these methods are useless if nobody knows the asteroid is coming.

"I think the best investment is in knowledge. The best investment is knowing what's out there," Binzel said.

That means completing a catalogue of near-Earth objects that could damage the Earth.

NASA is developing a space telescope to track asteroids

NASA/JPL-Caltech

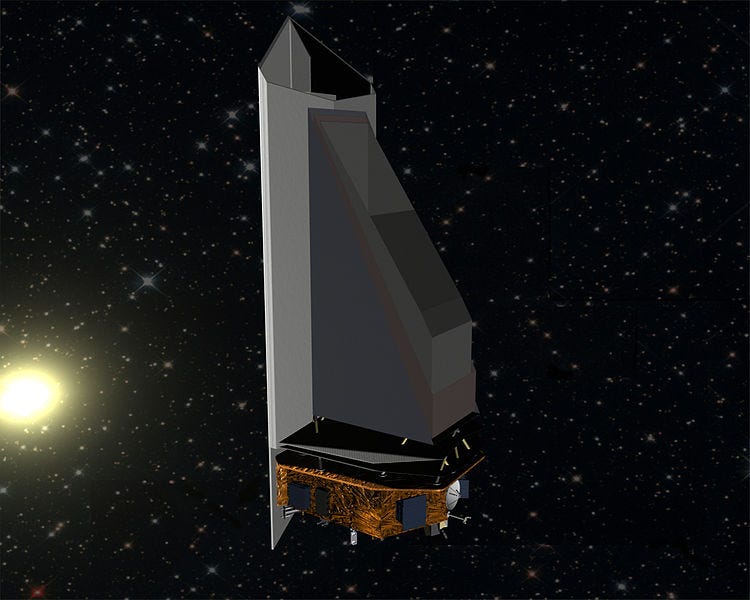

NASA is planning a mission to track down asteroids that are too dim for telescopes on Earth to see. The NEO Surveyor Mission, as it's known (NEO stands for near-Earth object), would launch an infrared telescope into Earth's orbit in 2026. Sonnet is on that mission team.

"If we do the job now of finding those objects and tracking them, knowing their orbits, knowing where they're going to head, and then characterizing their sizes, then we should be in really good shape," she said.

If the telescope launches and works as planned, it should fulfill NASA's Congressional mandate to find 90% of the most dangerous near-Earth objects.

But for five years, the NEO Surveyor has been caught in "NASA mission limbo hell," as Binzel put it. Due to insufficient funding, it hasn't moved past the early development phase.

Sonnett has her fingers crossed that the NEO Surveyor Mission will do well in an upcoming review. At the end of this month, NASA will assess whether the mission is ready to move into the next phase. If so, the team could start building prototypes and developing hardware and software. If not, the telescope's launch could be delayed even further.

"Because we now have the capability to detect and know what is out there, I think scientifically we have a moral responsibility to obtain that information," Binzel said. "It would be unconscionable that we were caught by surprise, by an asteroid impact that we could have seen coming."